A Story of Chernobyl Plant Liquidator That Wasn’t Included in the HBO Series

Hromadske journalists went to Pripyat with one of the liquidators, Oleksiy Breus. It was he who last pressed a button on the control panel of the fourth block.

HBO’s Chernobyl became the most successful series according to the IMDb portal ratings. The authors spent several years creating it. They spoke with eyewitnesses and perhaps for the first time showed exactly how the plant workers acted immediately after the reactor exploded. Even for Ukrainians who seemed to have heard and seen enough stories about Chernobyl, the series became a surprise. In particular, it turned out that two of the three liquidators-divers – Bespalov and Ananenko – survived (the third one, Baranov died). They live on Kyiv’s left bank where they received apartments after evacuation. Liudmyla Ignatenko, the wife of a fireman, is also alive.

The above-mentioned heroes are not the only ones in Chernobyl’s history. Hromadske journalists went to Pripyat with one of the liquidators, Oleksiy Breus. It was he who last pressed a button on the control panel of the fourth block.

Sound Sleep

Oleksiy Breus came to work at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant (CNPP) in 1982. He studied at the Moscow High Technical University. Before becoming the senior managing engineer of the fourth power block (just when it was launched), he worked at various engineer posts of the plant.

READ MORE: From the War Zone to Chernobyl

For the first two years, Breus lived in a hostel in Pripyat. Then he got a one-room apartment and moved to a nine-story building in Sportyvna Street. His neighbors were also employees of the CNPP. Behind the wall lives the lieutenant-fireman Leonid Khmil. Below them – engineer-mechanic Oleksii Ananenko, and above – senior engineer Leonid Toptunov. All of them were friends.

Oleksiy Breus at Chernobyl HUB in Kyiv, Ukraine on June 4, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / Hromadske

"I lived modestly. All there was in the room were a table, a sofa, shelves with books. I didn’t plan to make it home for long. In fact, I thought I’d move with time," says Breus.

From the engineer’s window you could see the plant. But that very day, on the morning of April 26, the man did not look out the window and went to work as usual, not even knowing what had happened. Even though in the middle of the night, his neighbor Khmil was called to extinguish the fire on the roof of the fourth block and to transfer water to the reactor.

The apartment where Breus used to live in the town in Pripyat, around 3 km away from the ill-famed Chernobyl power plant on June 3, 2019. Photo Oleksandr Kokhan / Hromadske

"I slept soundly and did not hear a thing," Breus recalls.

At about 7 a.m. Alex arrived at a bus stop near the house to go to work. He knew about the scheduled tests at the station, but it was his first working day after two days off.

"There were many people at the stop. Then, the "regular" bus of the head of the station shift arrived and called me up, and I went to work."

The bus was quiet, all the workers were silent. It was only when we approached the station that one of the workers said: "what’s with the block?". Then Breus saw the destroyed fourth block.

Breus poses inside his old flat in the Ukrainian ghost town of Pripyat. He jokes that he "didn't have time to tidy up." The drawings on the wall were made by him. Photo Oleksandr Kokhan / Hromadske

Radioactive Euphoria

"The building was half-demolished. It was a shock. My hair stood on end. It was unclear why they brought us here, what else could be done. But it turned out that for us, operators, there was still a lot of work," Breus tells Hromadske.

Breus immediately got to work – he had to estimate the scale of the destruction of the fourth block. From the ruins he passed, almost an imperceptible vapor rose up. He stepped over the pieces of graphite thrown out of the reactor.

At Breus’ control panel, the radiation level exceeded the permissible limit by a thousand times. But later he found out, this was perhaps the "cleanest" place he visited.

READ MORE: No Strangers Here: What It's Like to Live and Work at Chernobyl Power Plant

The damaged reactor number 4 at the Chernobyl power plant on April 27, 1986 (a day after the disaster). Photo Valeriy Yevtushenko / UNIAN

Breus’ main task was to feed water to the reactor.

At 9 a.m., when Breus returned from a dilapidated room, where he ran back and forth with his colleagues to open the water supply to the reactor, he had a sense of exaltation, celebration, and excitement.

"It seemed to me that I was capable of everything, ready to do anything at any cost. It was a 'radiation euphoria'," the man recalls.

At 11 a.m., Breus’ boss decided: everyone needs to vacate the fourth block at once.

"I returned to the block because Moscow officials kept ringing and demanded not to stop the flow of water to the reactor."

Oleksiy Breus speaks to Hromadske at Chernobyl Hub in Kyiv, Ukraine on June 4, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / Hromadske

About 4 p.m., the only pump that was working failed to turn on. Breus was the last one to press a button on the control panel.

"Thus our engineer work ended."

Breus worked a full shift – eight hours. Although the next few days it could last only a minute or a minute and a half for the operators.

A military dosimeter DP-5 that was used during the liquidation of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova / Hromadske

"In the evening, when I left the fourth block and took off my clothes, I was very surprised – the skin was brown in color, as if tanned, and my face and hands were red."

On that day, Breus received a dose of radiation exposure, which was almost 25 times the norm.

Fairytale Camp

Breus then worked at the third reactor for two more days. He cooled it and brought it to a stable safe state. While working, he says he felt seismic shocks from the fact that helicopters dropped sand onto the destroyed reactor.

Nobody was left in town. Everyone was evacuated outside the 30-kilometer zone. On the night of April 29, Breus and the rest of the operators went to the central square of Pripyat, from where they had to be evacuated.

Participant of the Chernobyl power plant liquidation process near the station's administration building in May 1986. Photo: Vasyl Pyasetskyi / UNIAN

"We were waiting on the bus and checking our watches all the time. Someone had an electronic watch – it showed an odd time – 72 hours 5 minutes. We realized that this was the result of high levels of radiation."

The bus departed in the morning. Several times during the journey it stopped – people got sick.

At dawn, the station workers were brought to a pioneer camp called Fairytale, within the 30-kilometer zone where they were accommodated. They were given some paperwork to do. To a small extent, they were also examined by doctors, who took blood for analysis, and did cardiograms.

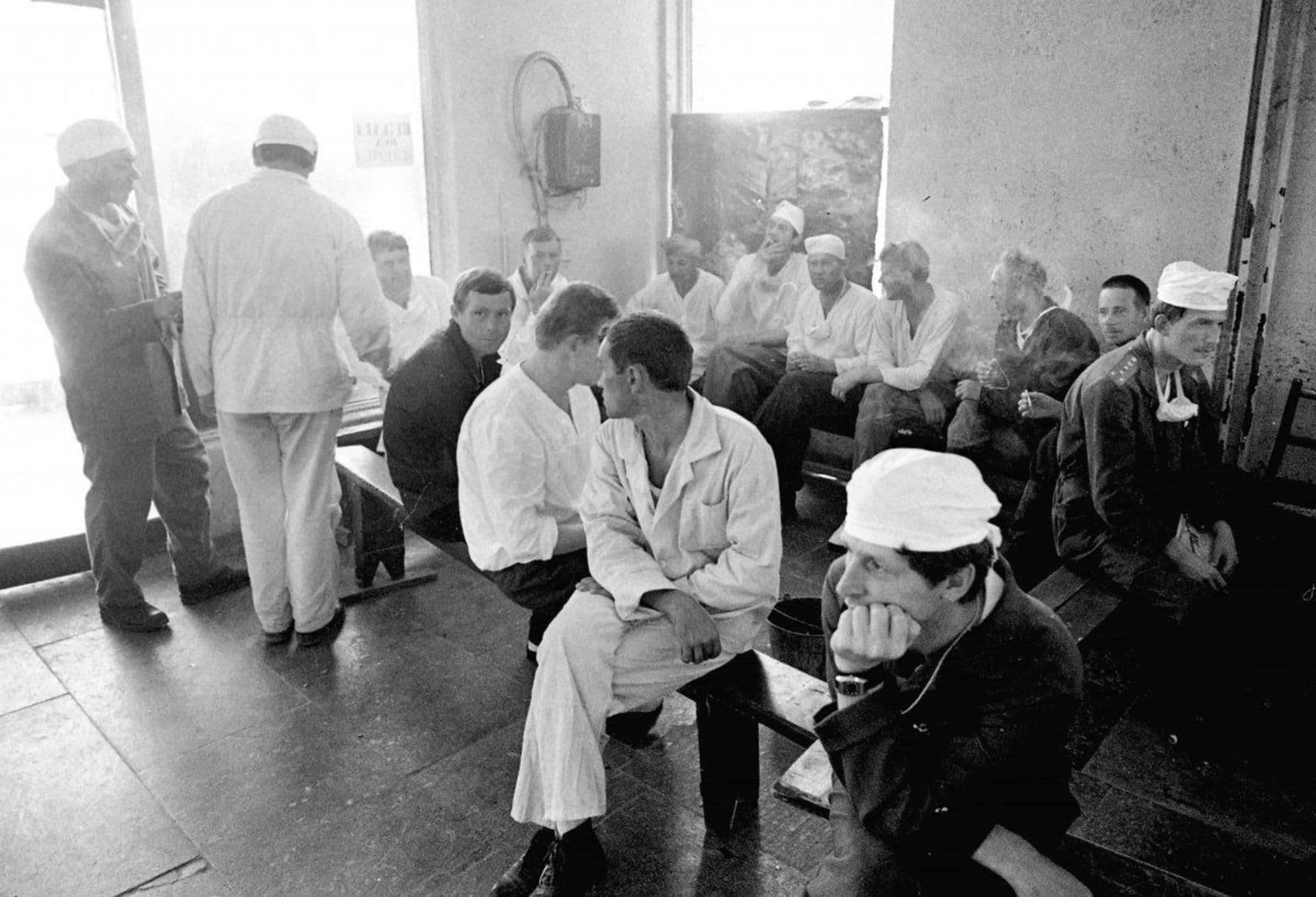

Chernobyl plant liquidators who worked in the tunnel under the reactor sit down during the change of shift in May 1986. Photo: Vasyl Pyasetskyi / UNIAN

READ MORE: New Life near the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

In mid-May, Breus was told that his services were no longer needed at the plant.

"I was told: take a vacation, go wherever you want. We will call you when we start work on the third block. I obeyed, but was never called again."

It was in August that Breus returned to Pripyat for the first time to pick up some things from the apartment. Especially the books he had a lot of.

Chief engineer of the Chernobyl power plant Mykola Fomyn (L) and deputy chief engineer Anatolii Diatlov near the control panel for the fourth reactor on December 20, 1983. Photo: Vasyl Pyasetskyi / UNIAN

"Pripyat was already fenced off with barbed wire. This was the first and only time when I shed tears."

In the summer already Breus began to feel changes in the body – a sudden weakness throughout the body.

"I was barely standing on my feet. And this state let go, then returned again."

Later, he found out that his dose of radiation was much higher than originally recorded. It was time to turn to the doctors.

"I was examined for two weeks, and they confirmed everything. I was no longer fit to work with radiation and began to look for another job."

Colored Chalk

In the first months after the Chernobyl accident, Breus had to sign a document for the KGB to not disclose information about the real causes of the reactor explosion.

"I did not like the fact that the employees were accused of the Chernobyl accident. They claim the workers made an error during the tests. In fact, the main reason was the design vulnerabilities of the reactor. And the repeat investigation in 1991 confirmed this."

This fact, says Breus, remains barely noticed. It was taken quietly and calmly because there was no emotional strain that existed in the first years after the accident.

"I do not want to defend my colleagues and shift the blame on the constructors of the reactor. My university lecturers were among those who designed this Chernobyl reactor. But the truth lies with the operator. He did not have enough information to understand the state of the reactor."

Breus poses during the event at Chernobyl HUB in Kyiv, Ukraine where he spoke on June 4, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova

This, according to Breus, is well-depicted in the Chernobyl series – the problem was in design flaws, not the actions of operators. It was only after the accident that they began to install devices on Soviet reactors that would show the parameters of the operational reserve of reactivity. Its deterioration led to the fact that the AZ-5 button failed to work as it should and did the opposite.

"It is important that the film directors managed to convey the magnitude, the globality of the disaster, the emotional state in which the participants of this event found themselves."

He admits there are drawbacks in the portrayal of the CNPP workers, though. In many episodes, they are depicted as cowards, scared stiff whenever the leadership appears.

"Actually, that's not the case. These were bold and decisive people. After the explosion, none of the operators ran away, on the contrary, they came in to replace those who worked at night. I also arrived in the morning. But it would have been nice if this series appeared a few years earlier and the truth was learned before."

Breus also fought to tell the truth about the explosion at the CNPP as soon as possible.

READ MORE: Chernobyl Through Decades: Life and Work

After being banned from working on radiation objects, he decided to go into journalism and write on the topic of Chernobyl.

"At first, I wrote and no one wanted to publish me. I thought I could not write well, so I went to study at university for two years. But it turned out that the problem was different – Chernobyl was a forbidden topic."

The Soviet Union, however, collapsed, Breus’ subscription for the KGB was invalidated, and he began to tell everything he knew.

The former engineer has worked for the newspaper Voice of Ukraine and information agency UNIAN.

In 2000, he grew an interest in painting and joined a group of independent artists Strontium-90, whose paintings are also devoted to the theme of the Chernobyl accident. Together they hold exhibitions and promotions.

Breus poses in front of his paintings in the Enigma gallery located in the Troyeshchyna district of Kyiv on June 4, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova

"In journalism, for quite a long time I touched on different aspects of Chernobyl, but never what I experienced myself. I never wrote about my own experience. As an artist, I have many more opportunities. I have no frameworks – I'm free."

There are several works devoted to the theme of Chernobyl in the gallery in Troyeshchyna, district in Kyiv, where the exhibition of paintings by Breus is currently taking place. One of them is an abstraction. Another one – shows an image of a red flower on a green background. There is a similar one in another place – in an abandoned apartment in Pripyat. It was drawn with colorful, bright chalk on the gray wall.

- Share: